First Generation

Born in 1755 on his father’s plantation in Edgecombe County, John Haywood first entered public service as the clerk of the state senate in 1781 before his election to the office of state treasurer in 1786, a position he held for forty years until his death. His first marriage to Sarah “Sally” Lee ended in tragedy, as Sally passed away in childbirth in 1791 with the couple’s only child, a son named Lee, succumbing to smallpox four years later. After a law was passed requiring all government officials to live in the new capital city of Raleigh, John relocated from the old capital of New Bern and married Elizabeth “Eliza” Eagles Asaph Williams in 1798 - the first of their fourteen children, a daughter named Elizabeth Eagles after her mother, was born later that year five days after Eliza’s 17th birthday. John then ordered the construction of a new house for Eliza located a few blocks away from Union Square; after the house’s completion in 1800, John and Eliza moved in.

In addition to his residence in Raleigh, John Haywood also owned at least two plantations: one in his home county of Edgecombe, and the other near Crabtree Creek in Wake County. Between 1798 and 1826, Haywood enslaved at least 124 people between these three properties. Exactly how many people were enslaved at each site at one time is unknown at the moment; documents in the Ernest Haywood Collection at UNC Chapel Hill’s Wilson Library list 65 people in 1823, but whether this list comprises just the Wake County properties or all three is unclear. Haywood also rented people from other enslavers in the area, using them to build Haywood Hall and other family homes - one rented worker, a man named Saul who was enslaved to W. Reese Brewer, was killed in 1800 in an accident while raising William Henry Haywood II’s house.

The Scandal

John Haywood’s new house quickly became one of the centerpieces of social life in early Raleigh. Supposedly boasting the second largest room in the city behind only the legislative building, the house saw visitors seemingly every night as John entertained constantly. Ever the socialite, John hosted the entire state legislature at his house at least once per session and sometimes invited throngs of people over unannounced - Eliza recounted a time in one of her journals where her husband brought thirty people over for dinner without letting her know in advance, much to her chagrin. Between the almost biannual pregnancies and constant visitors, Eliza felt relief whenever John took his guests out to eat to give her time to “just think and rest.”

John Haywood died of cancer in 1827, serving as North Carolina’s only treasurer in state history until that point. Upon his death, a committee of the state legislature investigated his office and found a shortage of approximately $69,000 in public funds. John’s estate was held responsible for the deficit, and nearly everything that was not deeded to Eliza was sold - personal belongings, land holdings, and enslaved people, among others. About $47,000 (half of which came from the sale of enslaved people) was raised from John’s estate; a further $7000 in bonds were transferred to the state after it was determined John’s executor, his son George Washington Haywood, had already given everything of his estate he could to the state. Left in debt and forced to charge her older children rent to stay in the house, Eliza survived her husband for five years before passing away in 1832.

Testimonies From the Enslaved

While not much is known about John Haywood as an enslaver, two notable sources describe his son, Fabius Julius Haywood. A doctor by trade, Fabius inherited a plantation in northern Wake County known as Oakdell from the family of his wife, Martha Whitaker. In 1860, Fabius enslaved a total of 47 people - 22 at his three-story house at the corner of Fayetteville and Morgan streets (listed in the Slave Schedules as “Dr Haywood”), and 25 at Oakdell (“G H Davis for Dr Haywood”). One of the aforementioned sources, Tama Spikes, was born enslaved to Fabius at Oakdell in 1860; the 7-month-old girl listed in the Slave Schedules on that plantation is likely her. In 1937, Tama was interviewed as part of the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal program in which unemployed writers travelled across the South collecting oral histories of formerly enslaved people. Tama recounted an instance involving her mother, Lucinda Wiggins: when the Union Army came through Raleigh at the end of the Civil War, some soldiers took food from Fabius’s smokehouse and told the enslaved people on the plantation that they were now free. When Lucinda relayed this to Fabius, he threatened to skin alive anyone who went in the smokehouse, further saying that the people he enslaved were not, and would never be, free.

More about Fabius as an enslaver is known thanks to the other source mentioned above: Anna Julia Haywood Cooper. Anna, her mother Hannah Stanley, and her two older brothers, Rufus and Andrew, were all enslaved to Fabius - whether they were enslaved at his house or his plantation is unclear, as a girl the same age as Anna appears at both sites in 1860. Hannah never revealed to Anna who her father was, as Hannah was “always too modest & shamefaced ever to mention him” according to Anna. She presumes, and historians agree, that her father was most likely her mother’s enslaver - Fabius Julius Haywood. Whether Fabius also fathered Anna’s brothers is unknown; if so, all three siblings were biological grandchildren of John Haywood and were enslaved by their own father.

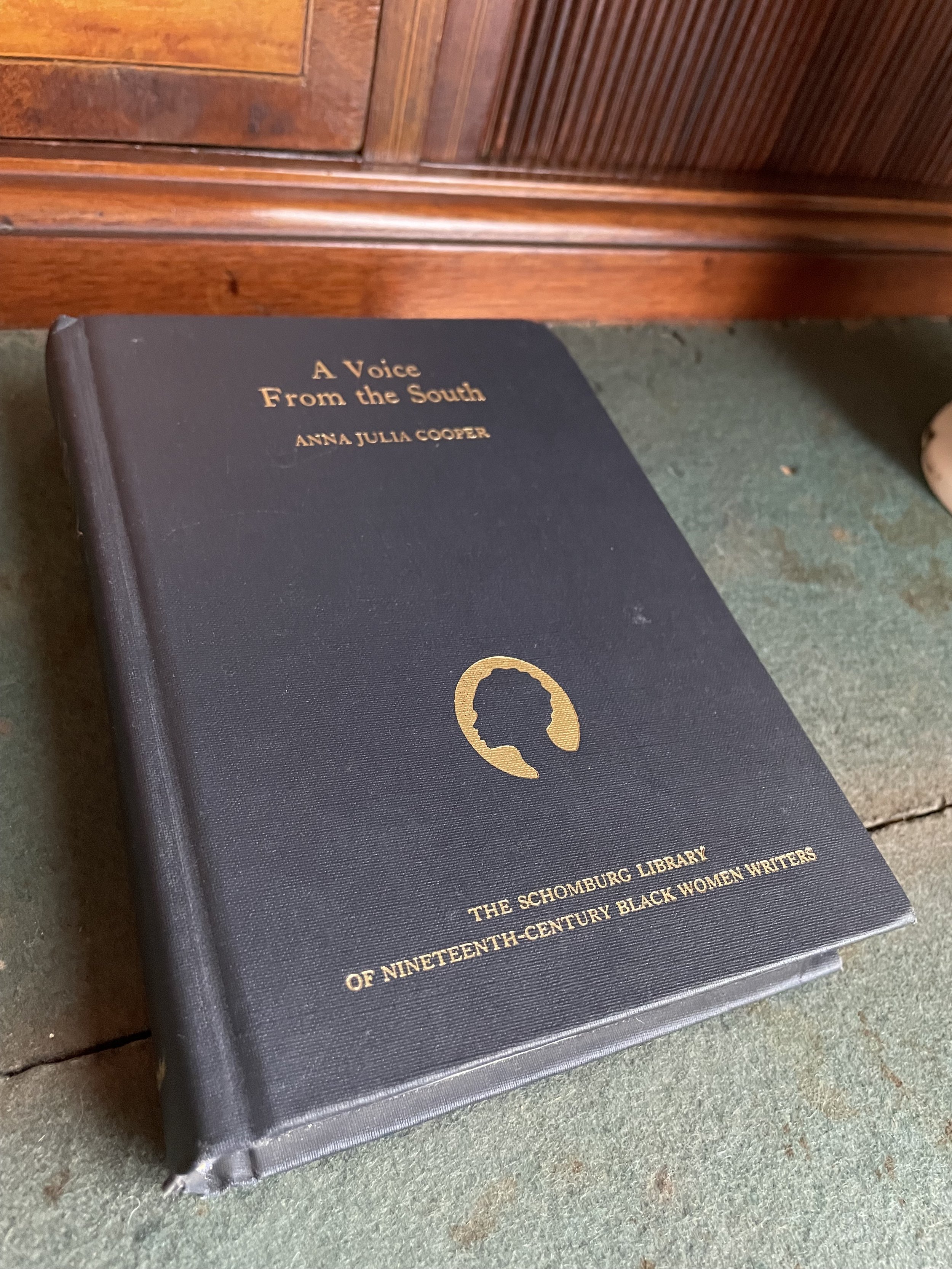

After emancipation, Anna attended St. Augustine’s Normal School and married one of her former teachers, Rev. George Cooper, upon graduation; George passed away only two years later, leaving Anna widowed at 21 years old. Anna furthered her education, earning a bachelor’s (1884) and a master’s (1887) from Oberlin College and finally a doctorate (1925) from the University of Paris, all while teaching at the high school and university levels. In addition to her work as an educator, Anna also wrote poetry and essays - her most noteworthy publication was A Voice From the South, published in 1892 and one of the earliest examples of Black feminist literature in the United States. Anna argued heavily in favor of the education and spiritual enlightenment of Black women, saying that doing so would uplift the entire race. Anna Julia Cooper passed away at the age of 105, just five months before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Her legacy as one of the most influential Black feminist writers in history was solidified with one of her most famous quotes’ addition to the U.S. passport: “The cause of freedom is not the cause of race or a sect, a party or a class – it is the cause of human kind, the very birthright of humanity.”

Second Generation

Eliza left the house to three of her daughters: Elizabeth Eagles (nicknamed Betsey John), Frances Anne, and Rebecca Jane. After Rebecca Jane married and moved to Wilmington, Betsey John and Frances Anne ran the house together for the next forty years. However, because Eliza’s will said the house had to be sold within six years of her death, there was one month where the house was owned by Haywood family friend and future governor Charles Manly; Betsey John used her siblings’ shares of the property sale to repurchase the house from Manly. During their ownership, Betsey John and Frances Anne operated a boarding school on the property, attracting the daughters of wealthy families from across North Carolina. After Betsey John’s death in 1877, Frances Anne continued to operate the school until she passed away in 1883.

Betsey John’s youngest brother, Dr. Edmund Burke Haywood, took ownership of the house upon his sister’s death - he had already been living in the house since his return from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in 1850. E. Burke married Lucy Ann Williams, daughter of local merchant Alfred Williams, and all nine of their children were born and raised in the house. A surgeon by trade, E. Burke became involved in mental health later in life; he was appointed to the board of directors at Dix Hill (later Dorothea Dix Hospital) and was instrumental in the establishment of both Cherry Hospital in Goldsboro and Broughton Hospital in Morganton in the 1880s. After his death in 1894, E. Burke’s widow Lucy took ownership of the house and made several changes: indoor plumbing, porches on the rear and west sides, and a gazebo were all added; outbuildings were moved to the back of the house; and nine family graves were moved to Oakwood Cemetery.

Third Generation

Upon her death in 1920, Lucy divided her estate seven ways among her surviving children: brothers Ernest (a lawyer) and Edgar (a businessman) received equal shares of the house and surrounding property. Aged 60 and 58 respectively at the time, both brothers lived in the house their entire lives and never married. Unfortunately for Edgar, his co-ownership of the house was short-lived. The same year he received his share from his mother, Edgar fell from a horse while fox hunting and broke his neck, leaving him paralyzed and confined to the northwest bedroom of the house; Edgar died of cancer four years later, making Ernest the sole owner of the house.

Later in life, Ernest became infatuated with air travel. In 1937, aged 77, Ernest made plans to travel around the world via multiple forms of air travel. Along with airplanes and clippers, an airship known as Hindenburg was supposed to carry Ernest from Germany to South America; Ernest learned of the Lakehurst, New Jersey disaster while on his trip and was disappointed airship travel was no longer an option. Completing his journey in two legs, Ernest was aboard one of the last transatlantic flights out of France before the outbreak of World War II in 1939. Upon his return to Raleigh, Ernest remarked that he was “grounded for a while.”

While his circumnavigation of the world made local headlines, Ernest made national headlines due to an incident in 1903 which resulted in the death of John Ludlow Skinner, the son of a prominent Baptist minister. According to witnesses, the two were engaged in a conversation in front of the post office on Fayetteville Street when Ludlow struck Ernest, knocking him to the ground. As Ludlow reached into his coat’s left pocket, Ernest pulled out a pistol and fired twice, with the second bullet entering Ludlow’s left side near his rib cage - he staggered into the middle of the street before collapsing dead on the trolley tracks. Upon investigation, a loaded pistol was found in Ludlow’s left coat pocket, and Ernest’s defense was able to prove to the jury Ludlow was reaching for his gun when Ernest fired, acquitting Ernest of first-degree murder charges by reason of self-defense.

Fourth Generation

Ernest Haywood passed away in 1946, leaving the house to his brother John, who then turned the house over to his nephew Burke Haywood Bridgers - a lifelong Wilmington resident with no plans of moving to Raleigh, Burke finally sold the house to his cousin Mary Haywood Fowle Stearns, the daughter of former governor Daniel Gould Fowle. Mary Stearns’s mother, Mary Haywood, was the daughter of Fabius Julius Haywood - as the great-granddaughter of John Haywood, Mary Stearns marked the fourth generation of Haywoods to inhabit the house built in 1800. Mary and her husband, Walter Stearns, were retired and lived in Schenectady, New York at the time - the couple was looking to move to the Raleigh area where they previously summered, so the timing was ideal.

Upon moving in, Mary and Walter made the decision to furnish the house not with the modernities of the time but rather with antique furniture from the early 1800s, modelling the house after what it might have looked like when John and Eliza Haywood lived there. Mary also christened the house with its name: Haywood Hall. While living in Haywood Hall, Mary and Walter conducted research on the house’s architecture and family genealogy, with their efforts resulting in Haywood Hall’s recognition as a Raleigh historic site in the 1960s. After Walter passed away in 1957, Mary continued to live in Haywood Hall until she herself passed away in 1977, aged 98. In her will, Mary bequeathed the house to the North Carolina chapter of the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America (NSCDA) as a “place of historic interest for the public,” stipulating that no furniture already in the house was to be sold and authorizing any and all repair and restoration work necessary. The Dames have owned Haywood Hall ever since, operating both as a historic house and as an event space, with weddings in particular drawing the bulk of the interest.

The Path to Freedom

One of the people enslaved by John Haywood was a man named Edward “Ned” Lane. Haywood purchased Ned from the estate of Joel Lane in 1800, working Ned as the head gardener on the property. Ned’s wife, Clarissa, was enslaved by Sherwood Haywood, John’s brother who lived close by - Lunsford Lane, Ned and Clarissa’s only child, was also enslaved by Sherwood. Born in 1803, Lunsford realized as a teenager the realities of his situation; Sherwood’s children, whom he had grown up playing with, began bossing him around and were permitted to learn how to read and write, while Lunsford was not. While thinking of ways to escape this situation, Ned gave Lunsford a basket of peaches which he promptly sold, earning Lunsford the first money of his life - his plan became to purchase his own freedom. Eleanor Haywood, Sherwood’s widow, agreed to emancipate Lunsford if he raised $1000, which he raised primarily by renting out his work to other people around Raleigh and by selling homemade pipes and a special blend of tobacco he and Ned formulated. While raising this money, Lunsford lived in the barn on John Haywood’s property, currently located behind the main house. Lunsford purchased his freedom from Eleanor, and after travelling with a friend to New York, he was officially free.

Ned Lane also gained his freedom around the same time as his son as he was emancipated by Eliza Haywood in her will. Lunsford, however, still had a wife, Martha, and seven children held in slavery. In order to raise money to purchase their freedom, Lunsford participated in abolitionist debates in the Northeast, passing his hat around each audience to accept donations. After raising enough money, Lunsford returned to North Carolina only to be arrested under the presumption he was there to spread the word of abolitionism. He successfully argued out of the charges, but before he could reunite with his family, a mob took Lunsford into the woods - instead of lynching him, they decided to tar & feather him. Surviving the encounter, Lunsford finally purchased his wife and children out of slavery and escaped to the North with the help of some friends; Eleanor Haywood also let Clarissa, Lunsford’s mother, go with him. In 1842, after his father Ned joined him in Philadelphia, Lunsford published The Narrative of Lunsford Lane detailing his life up to that point. Lunsford Lane lived to see the end of slavery, passing away in Greenwich Village, a neighborhood of Manhattan, in 1879.

Guided tours of Haywood Hall are offered every Wednesday at 11:00 AM, 1:00 PM, and 3:00 PM. Tours are free of charge and last between 60-75 minutes depending on questions and the weather - no reservations are required on Wednesdays. Tours are also available by appointment if Wednesdays are not an option for you or your group.

For more information or to schedule a tour, please contact info@haywoodhall.com.